George Jetson was fictionally born this past July, and we don’t have self driving, let alone flying cars. There aren’t even robot butlers yet, but Boston Dynamics is getting pretty close with the mechanics.

What’s missing is that the artificial “intelligence” we typically interact with has the IQ of a Roomba or auto-correct. It’s really hard to imitate the unique work of a human. Writing, drawing, and even a simple conversation is a generative creative moment.

We’re getting closer though. While still very much in novelty form, technology like GPT-3 and its image generative implementation DALL-E are creating incredibly powerful and thought provoking original content. GPT-3 takes written prompts and generates eerily cogent text, while DALL-E uses those same natural language inputs to create a series of images.

The best examples could easily pass the Turing test, and there is a deep, reflective humor shown in the creations that are just *slightly* off. It feels like we’re but a stone's throw from real commercial applications here - even if it just starts with the sketch comedy business.

At the risk of oversimplifying how the technology behind this works, it’s just a lot of reps on the trainer. When models and algorithms learn, they are consuming a lot of data and generating truths from all the inputs they chew through. They are designed to predict what the next token is going to be in a series. If you show a computer algorithm one thousand pictures of Bazooka Joe and Doublemint, it’s going to be able to produce a pretty accurate creation of bubble gum.

A major risk of generative content is that it is subject to the garbage in, garbage out problem. These models are only smart enough to mimic what they find, and the internet provides a lot of dubious quality information.

Wikipedia is used as a core training document for language models because of the variety and accessibility of its content. When it turns out that the majority of a language’s Wikipedia has been fabricated by a tongue in cheek prankster (e.g. the American who made over 20,000 edits to Scots Wikipedia articles in his own imaginary Scottish accent), you’ll want to double check any internet translator’s output.

If the sample size is small, the models don’t really have much to work with. I was playing around with one of the image generators, NightCafe, and punched in a truncated description I have for The Till. “Newsletter about investing, options, wine, and crypto.”

On the left you have the image from the page on my website describing the Till. On the right you have what NightCafe produced. That syntax is unique enough that there’s really only one sample, and the AI just ran with what they knew about my single image, and newsletter graphic design. The writing looks like some newly discovered ancient runes.

An alternate model produced something entirely different, which shows a bit about how they’re constructed under the hood. The version from Craiyon, parses the words individually and comes up with this collection. Lots of wine and crypto, not many options or soothing verdant rows.

Both are examples of what the average use of those words are on the internet. One is those words combined, for a sample of one, and the other is the average picture of wine or digital money, perhaps blended together. There is an unsettling dimension to how the algorithm averages something pervasive like the Bitcoin logo.

Data hungry algorithms are going to consume everything they can to come up with the most “accurate” picture or text for the prompt. They take the most common attributes and use their mean color and median size to reverse engineer the Platonic ideal hidden in a billion examples. In AI, mean and median are a lens into the truth.

For most purposes this is very effective and powerful. There’s a lot of generic images or text that don’t necessarily need to be created by humans (e.g. background art in video games or drafting legal documents. ) There are risks to unsupervised implementation, but passing off the low hanging fruit to technological advancements is the purpose of innovation.

The tenants of passive investing generally also support the idea that the average is the most pure or true exposure. Much like AI seeks to determine what the objective truth of a brush is by combing over every possible image of a brush online, passive investment in market benchmarks seeks exposure to the “true” representation of that risk asset class.

I’m oversimplifying both here. There is interesting weighting in AI algorithms that teaches it to trust certain sources over others, just as there are clever ways to accurately reflect the market through index design. DALL-E uses 12 billion parameters and index committees think long and hard about weighting and construction.

The theoretical justification for passive investing leans heavily on the efficient market thesis. The price of a security is an accurate representation of its value because the competitive and financially incentivized population have incorporated all available information into that price. To the extent that we validate the outputs of these AI models, it’s because they rely on the fact that most highly ranked images tagged with chair or bubblegum are going to an accurate representation of that word’s meaning.

If you diversify your holdings across the largest companies and rebalance periodically, over the long run you will not only benefit from the equity risk premium, but you’ll beat most people working nights and weekends focused exclusively on buying and selling stocks. Fewer than 8% of managers have beaten the market average over the trailing 15 years. Compound the mean and you’ve got a good shot at the 1%.

For vanilla equity exposure, it is cheaper and more effective to let a (much simpler than AI) algorithm give you the average. We’re getting to a point where it will soon be cheaper and more effective to get the “average” content for your document draft or set design thanks to these rapidly developing tools.

For the artists, lawyers, and active fund managers who were offended by the idea that their jobs could be automated - there is still room for rebuttal. There’s still plenty of demand and opportunity for the qualitative spin of human touch.

My goal as an advisor is to work with product building blocks that sit on top of this vanilla exposure, and tailor the risk profile with options to better match individuals' tolerance and capacity. The human value add comes after the algorithm does the part that algorithms are good at.

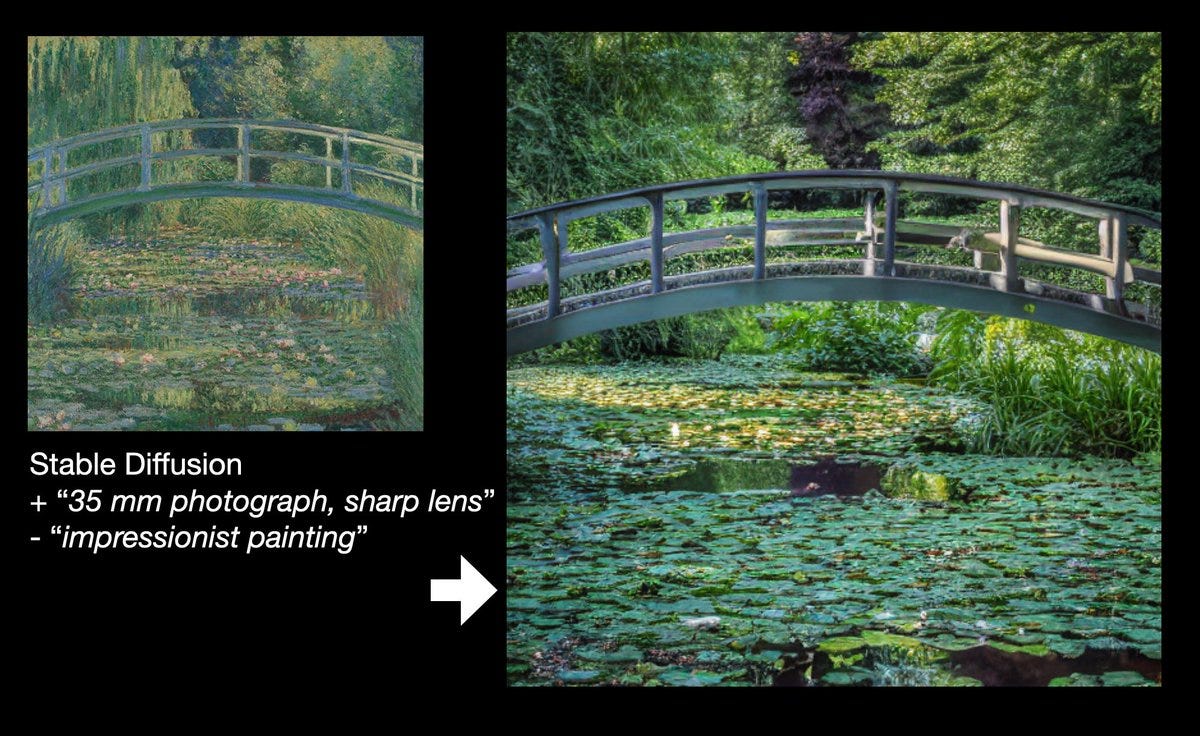

Some of the recent DALL-E creations have also inspired another investing lesson. One of the clever and humorous ways the technology has been used is to scrub famous paintings to de-impressionize what Picasso or Monet were really looking at.

While the images on the right are creative and interesting because of their context, they are much closer to “average” art. Monet and Picasso are lionized precisely because their work is exceptional in its brush work, coloring, and overall creative interpretation.

A computer algorithm can turn something unique into something average, but I’ve yet to see an example of it creating something truly artistically praiseworthy. A romantic might say that’s because a machine can never understand the human condition, while the futurist says “not yet”. Some of them like the David DJ’ing are pretty good though…

The investor takes the twofold lesson that it is both rare and difficult to have any distinct “alpha”. If the market is going to beat 92% of active traders, and all the information is priced in, you’d better have a rock solid edge in your craft and analysis. Durable edge is a journey, not a destination.

You won’t sell a painting of Haystacks for $110M that’s based on a paint by numbers. But you can decorate your house quite stylishly with low cost imitations of famous art or furniture styles that serve their technical purpose just as effectively. (This may or may not be a trigger to see if my wife reads this blog.) In decorating, finance, or AI, when most people go off the beaten path, they’re far more likely to end up on Zillow Gone Wild.

What really separates the best from the rest is an ability to think truly independently and not get reverted to the mean. Humans still can laugh at the quirks of AI facsimiles, because they haven’t yet been able to intelligently create uniqueness.

Lawyers still need to review drafts of contracts because every situation is unique, and can fail in ways only a human can imagine. True artists will still be the ones creating the coherent but uncomfortable bleeding edge works. These are both professions where being unique is a distinct advantage and rewarded.

While truly distinct and superior money managers are well rewarded with capital and fees, for most individual investors, average is best. You don’t even need a multiple regression supervised model to do that.

Perhaps GPT-3’s next challenge to tackle will be identifying better index construction or diversification techniques. I’m all ears for tools that let computers do what computers are good at. The Monet’s of their profession will always be pushing the bleeding edge of creativity.

According to one famous Wall Streeter there’s still an open challenge to artists; “I've never seen a painting that captures the beauty of the ocean at a moment like this.”