Clocks are everywhere.

Even if you aren’t flexing a Rolex, the ubiquity of cell phones means we all have a pocket watch. The laptop, the microwave, or a nice large grandfather can all tell you the time of day. I even have a little one directly facing the shower.

It’s pretty easy to tell - but do you actually know what time it is? Absent the constant reminder of every ticking second, it can be pretty hard to keep track. Particularly because if you’re fortunate enough to leave the device out of reach, you’ve entered a long form attention span.

Losing track of time is usually a blessing - you’re engrossed in an activity, not forcing passage by logging sheep. Except when it's - “honey, do you know what time it is?” No matter which word you emphasize, that phrase is a test.

I like to think I have a pretty good internal clock. Not just because I consistently wake up before the alarm, but because telling time is a 24/7 parlor game. It’s important to be on time for your lunch reservation, and the guess is immediately validated by an objective truth.

“11:30?” “11:22.” Nice. Early and accurate. An eight minute difference is rough if you just stood up from a desk with 4 monitors, but it’s pretty close after two hours in the yard.

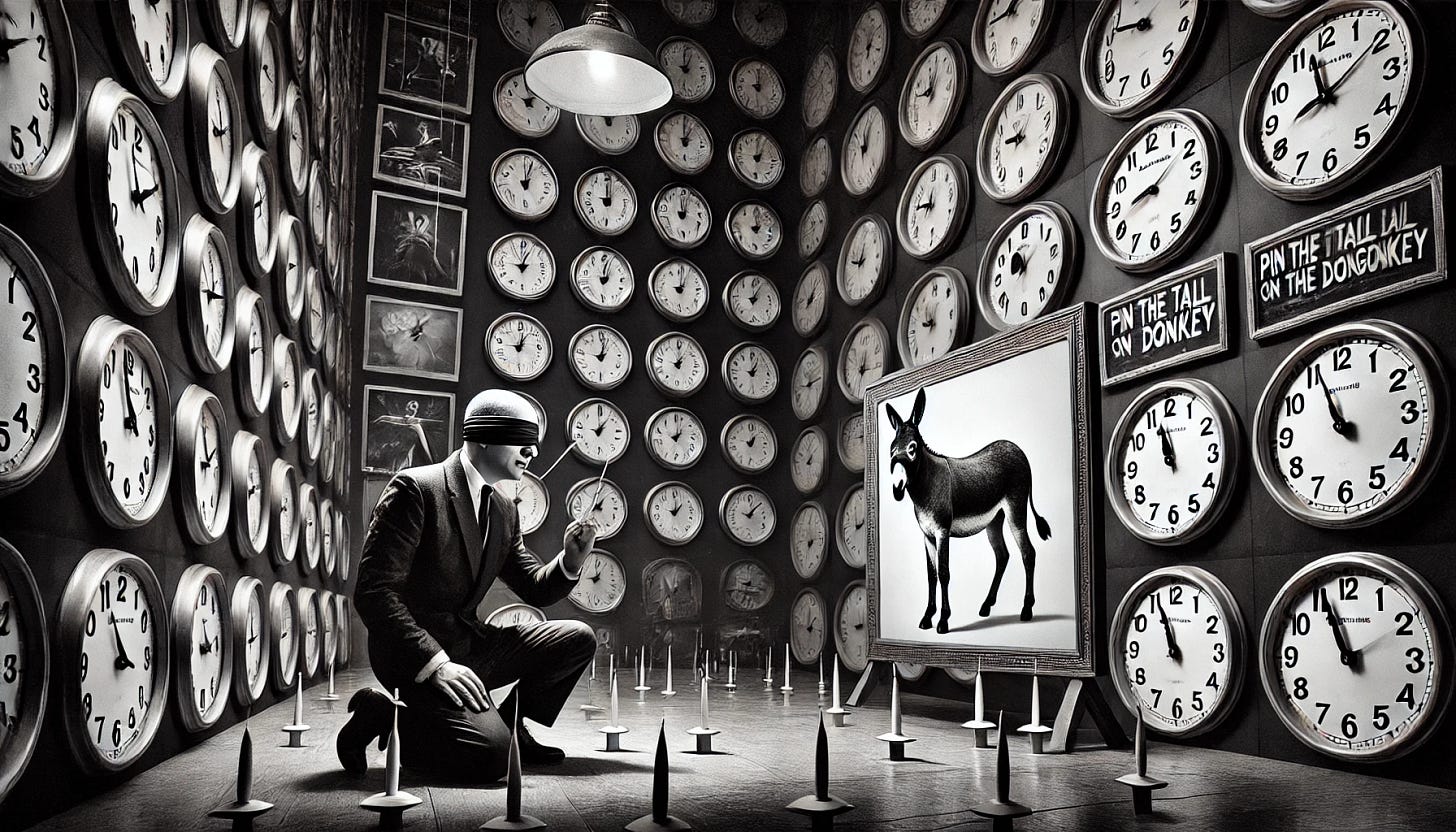

A good estimation is a very valuable tool. And it’s a skill to be refined. I’m not cheating with a sundial, but using context clues and experience to pin the tail. Since the last anchor point - what’s changed, how long should that have taken? Are they back from the grocery store already?

The starting point for valuation is an educated guess. Stick a finger in the air - you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows. Any guess is a good one, so long as you follow two simple rules.

The first is not to get married to your position. You cannot be so emotionally attached to this estimate that an update to its value becomes an assault on your ego. (That’s also Colin Powell’s third rule of leadership.)

The purpose of an estimate is not to nail the answer. It’s a kernel to seed the iterative process of truth seeking.

While it is important to have a reasonable starting point, the real value add is the process used to converge. Whether you’re an LLM, options pricing model, or human - find a process to correct your error term.

A good estimate must also have a confidence interval. Most models only output a single answer, but we need to consider the significant digit roughness of each component. In the options model stock price is precise, but expected volatility has quite a bit of fuzziness to it. More as you decrease in liquidity.

This is why market makers put spreads - i.e. quotes - around their fair value. It reflects the cost of managing that uncertainty and error term. But even for a naive guess about the time until lunch, knowing how big your error term could be matters.

Estimating is learning about uncertainty. We need it when we suffer from clock deprivation, and when trying to predict the future path and value of a security. By having a nimble perspective on value, and quantifying your certainty, you learn, and get better at learning.

Guessing the time is but one instance of the enormous class of parlor games around estimation. A perennially appropriate, quant’s version of “I Spy”. Start betting on the value of just about anything. Next person to come out the door - man or woman?

Traders turn everything into a gamble because they want the dollars from the action, but they also want to be a better bettor.

There is an art and a science to coming up with a theoretical value. A more nuanced model with higher quality inputs will produce a better estimate. With earnings season coming up, there are thousands of little laboratories to test your predictive edge. The variance bomb that gets dropped on a single day drives far more volume than the lazy vacillations of (most) market days.

Earnings is all about movement - and with weekly options you get narrow exposure to the impact of a specific event. How much will AAPL move on earnings? Is the $8 straddle over or under priced? One way to do that is to look at all the past earnings - how much does it usually move? Maybe you contextualize this by vol environment - a 10% move when VIX is 12 is a perhaps more significant than when VIX is 30.

The art comes in with these adjustments. Only with the experience of many bets, do you know exactly how to feather the nuances with subjective variables.

Now that we have models that learn themselves, there is insight in how they adapt. At the algorithm level, tools like GPT are simply making predictions about what the next word should be. They consume massive bodies of text, and begin to predict what words should be used in what contexts. By comparing this to the truth, they adjust the weights based on the gradients with the steepest error function. Iterate, rinse, and repeat.

Focusing on your largest error is an act of humility. But the only way you’re going to get better at predicting the next word or estimating the number of times the word “thank you” gets used in a risk call is practice. Playing estimation games keeps your spidey sense limber for when something more important is on the line. It’s also fun.

Even if you don’t have a precise formula to come up with an error term, it’s a fruitful activity. Questioning your confidence and valuation process is the foundation of sizing your trades, bets, and emotions.

It’s pretty unfair to your zen to get upset about something you can’t confidently predict. (Market returns not excluded.) One of the most devilish things that rideshare has done to the world is trying to estimate when your car is going to arrive. You knew there was a fat error term when the cab company always just said “5 minutes” and they arrived between 2 and 10 later. But staring at your phone while a driver diddles around a parking lot is infuriating.

The best part of estimation games is that they’re totally free. Sure you can put money on the line to keep it interesting, but you can also play all by yourself. It’s the smallest and most flexible play account possible.