One bad apple can spoil the bunch. But a single AAPL can have a powerful impact on your portfolio.

The first part isn’t just grade school wisdom about how a sourpuss will ruin group dynamics, it’s a scientific fact. When fruits ripen, they emit a hormone called ethylene that serves as a ripening agent. A rotten apple will cause the rest of the apples to mature more quickly. This is the same reason that putting avocados in a paper bag gets you guacamole faster.

What’s good advice in the kitchen, is also good advice for your portfolio. (See also: you can’t bake a cake twice as fast at 2 x 350 degrees, too much risk will burn your cake and your savings.)

While a single rotten apple turns the barrel, a single big winner can dramatically change the texture of your portfolio. I was recently discussing single stocks with a client, and he said “any mistakes I’ve made investing have been covered by the fact that I’ve been long AAPL since 2010.” It got me thinking about the significance a single investment can have on a portfolio.

Good investment management is about walking the tightrope of risk and reward. It’s a delicate balance of finding high returning big winners and capping the downside of a dog with fleas. The reason low fee index tracking ETFs consistently beat the professionals is that they have a systematic process of concentrating on the winners and dropping the losers through a quarterly rebalance.

Many people know that the stock market has compounded at something like 10% over the past hundred years. Therefor stocks sound like a great investment until you start digging into how the individual names perform.

A fascinating 2018 paper from Hendrik Bessembinder called “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills” lays clear the stark reality. More than half of stocks deliver a negative real return over their lifetime, the single most common outcome for a stock is a loss of 100%, and the average lifetime on the public marketplace is only seven and a half years.

Further exaggerating this effect is the fact that a small selection of names account for nearly all of the growth. The top five firms (Exxon Mobile, Apple, Microsoft, General Electric, and International Business Machines) produced 10% of the wealth creation. The top 90 firms (0.33%) generate 50% of the wealth, and the top 4% create all of the positive equity wealth during the last century.

It’s easy to look at a name like Apple or Microsoft with hindsight, but the bulk of that wealth creation comes from having conviction early on. Amazon went from over $90 to under $9 in an 18 month period after the tech bubble popped in March of 2001. Many more sellers than buyers, yet even a $90 buy and hold would have compounded at 17% over the last 23 years. (If you paid $8, it would have been a 32% annual return. The price you pay is the most significant factor in determining outcomes.)

The same effect is true in venture capital. The data below from Andreessen Horowitz shows that only 6% of deals done produce over 60% of the returns. Over 50% of the deals are net losers, returning less than the investment amount.

We have two pieces of conflicting data here. On the one hand, the right investment can single handedly change your life. Just ask Lance Armstrong about his Uber windfall. On the other hand, we know the vast majority of investments are rotten apples.

Here is where the arithmetic gets fun. Adding a little bit of different to your portfolio can have an outsized impact, without being too punitive on the downside. It all comes down to right sizing.

I’ve advocated before that “play money keeps you interested.” Doing the boring investment thing is really hard in isolation, but if you keep your whistle wet with a small allocation to fun and speculative investments, it’s a lot easier to understand how important it is to stay the course for a nest egg.

When you allocate 5% of your portfolio to a speculative investment the worst outcome is that you only have 95% of your safe investment. Stocks are capped on the downside. The reason options pricing uses the lognormal distribution is because there’s a wide open right tail (upside), but everything stops at 0.

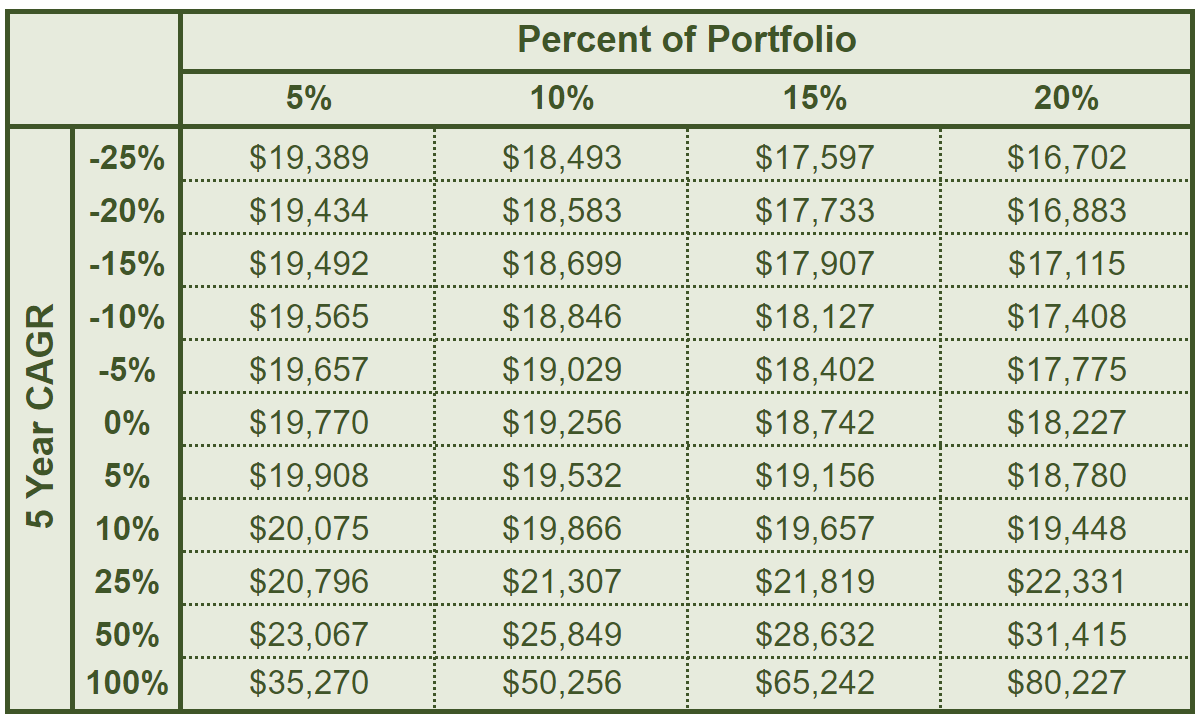

Looking at the below table, we have the allocation to speculative investments on the horizontal axis, and the returns of those investments on the vertical axis. The value in each cell assumes you allocate X% to the speculative portfolio, and the remainder to the S&P 500.

Over the course of the last 5 years the S&P 500 has a total return of 15.19% per annum, and these values are for a $10,000 portfolio. Assuming you did nothing but invest 100% in the stock market, your control balance would be about $20,284. That’s not a bad return at all!

A negative 25% return per annum means you’re left with only about 25% of the original value after 5 years. The loss curve starts to flatten in dollar terms, but a stock that has lost 90% of its value, still can lose 90% more before going to 0.

Allocating only 5% of your portfolio to a speculative and volatile asset has a certain asymmetry. Losses are dollar capped, but big winners can quickly run and create an outsized impact. A 50% CAGR (compound annual growth rate) is a 7.5x return on your investment over five years.

While a 100% CAGR sounds absurd, that’s about 9% lower than what Bitcoin has done in the last 5 years. Allocating only 5% of your portfolio to a highly speculative asset, would have left you with either a 14% CAGR if it went to 0, compared to the 15.2% if only invested in the stock market. However when that volatile asset increases by over 40x, just a 5% allocation gives you a 28% CAGR, and 2.5x the cash on cash returns from the index benchmark.

The effects are more extreme the more you allocate to the speculative part of your portfolio. 20% of a portfolio would be a very risk acceptant allocation to speculative assets. They are highly volatile for a reason, and the negative compounding of too many flops can be a major drag on performance.

Consistently underperforming the S&P 500 puts you at risk of falling behind inflation, and not being able to use money for what it’s for - funding goals. But risk managed dabbling, lets the long right tail do its work.