I’m a part time writer on sabbatical in Paris. This means I spend most of my time drinking wine and reading books. The Sun Also Rises.

My current distraction is the book “Oil!” by Upton Sinclair, which after turn of last century censorship battles, rose to rekindled fame when it inspired the movie “There Will Be Blood”. Daniel Day Lewis and Paul Dano absolutely crush the interpretation. It’s now fifteen years old and eminently rewatchable. The book is just as worth it.

J. Arnold Ross is a self made oil tycoon who travels through Southern California tending to his wells and prospecting for black gold. He and his son Bunny have followed a hunch down to a little known corner of the state, where they spend time camping and imitating leisure. After a few days of befriending the locals under simple pretenses - low and behold - an earthquake unlocks some of the precious sweet and sticky that burbles up out of the ground near their tent.

This must be kept extremely quiet. News of a strike travels quickly, and invites not only competition but significantly higher prices. For J. Arnold to maximize this opportunity, he needs to purchase as much territory around the strike as possible, to box out his rivals and ensure he has every potential angle to drill from and suck the oil sand’s milkshake dry. The land must be stealthily acquired before anyone is the wiser.

As a brief literary aside, the narration from Bunny provides interesting context and highlights Sinclair’s satire. The boy regularly muses to himself about the ethics of his father, wondering if greasing the wheels of county road commissioners and speed cops is good civics. He also struggles with the concept of a fair price for the land, when he and his father clearly have inside information. This however is all quickly distracted by the prospect of himself being a millionaire ten times over.

While Ross is only a small timer compared to the “Big Five”, this oil man has enough of a reputation to carry letters of credit in two different names. When it comes time to buy, he needs to do so quietly, lest anyone know what the smart money is up to. James Ross might be able to pick up some rock strewn quail hunting territory for $5 an acre, but if J. Arnold shows up, the price will quickly multiply.

Upon meeting the local real estate agent and informing him of his plan to acquire every tract possible, he gives detailed instructions about how to proceed:

“Of course as soon as people find you want it, they begin to boost the price; so let’s get that clear, I want it jist enough to pay a fair price, and I don’t want it no more than that, and if anybody starts a-boostin’ you jist tell ‘em to forget it, and I’ll forget it, too.”

- Upton Sinclair, Oil!

The patience Ross displays here would make any execution trader envious. While we all know that negotiation 101 says you should always be prepared to walk away from a deal, the heat of the moment or thrill of discovery too often takes control. He can afford it, why not just pay it and move along?

Human nature tricks us into rushing to get things done. Whether it’s buying a single share of stock or a house, everyone knows the sensation of watching prices move between the time you decide to buy, and when the buying is done. Navigating between these banks is the dance of execution, where currents are liable to change direction at any given moment. Thrilling for a few, terrifying for the rest.

The price that you receive is a function of the liquidity at the time of execution. Liquidity develops from market participants making judgements about security specific factors, macro sentiment, and observing the behavior of other players to come up with a price and size to show at that moment. Knowing that your neighbor is getting offers is sometimes all the information you need.

Ross is trying to find good liquidity by taking advantage of a fragmented market place and asymmetric information. Each of the sellers will agree to deal at the going rate of $5 per acre if they assume there is only one transaction, and that the generally accepted rate before J. Arnold showing up is still reasonable. This tactic isn’t exactly illegal - Carl Icahn is a big fan - but it comes with some notoriety.

Knowing who is doing the buying is an important piece of information. Smart paper is the enemy of any liquidity provider or land seller, who instead of just pricing random transactions is now dropped with the wrong side of some yet unknown.

The size of the order relative to the market is also very important. When you’re looking to buy ALL of the land you can in the hills north of Huntington Beach, you can assume that the price is going to move quite a bit.

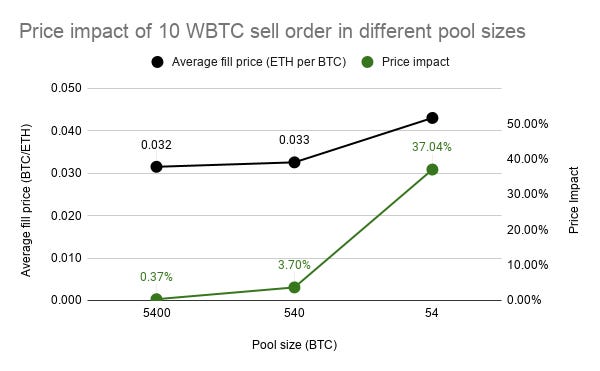

The automated market makers of DeFi handle the decentralized liquidity problem in an interesting way that is instructive for small pools of liquidity. Using the revolutionarily simple constant product formula, they value the price between two assets based on the ratio of those assets in a pool. When a trader makes a transaction, they put in one to take out another, the relationship and thus the price between the two assets changes. The price impact that order pays is a function of the size of the pool relative to the size of the order. Any two assets can trade this way, so long as someone starts the pool by putting in equal amounts of both.

The below chart shows how much price impact a trade would receive for various size orders. When you’re trading 0.20% of the pool, you only have 0.37% impact. When you’re 20% of the pool, you’re going to have a 37% price impact. The curve goes out to infinity, because every incremental piece you buy raises the price jist enough.

J. Arnold was trying to buy the whole (oil) pool. Even if he was only looking to get 75% of the land, if he had to do this through an automated market maker, his price would be $20/acre instead of $5/acre (full math below). DeFi has some fantastic innovations, but handling large sized orders relative to liquidity is not its strong suit.

This is where brokers - real estate, equity, or options pit - can provide a real service. J. Arnold had his broker ping all the various sources of land liquidity, the same way a stock algorithm pings the various dark pools and sources trade liquidity before each offer can see that the other has been taken out. Whether time moves in days or picoseconds, the game is the same. Get your order done, balancing the dual mandate of quiet and quick.

People often ask what the purpose of the trading floor is these days. The CBOE just recently opened up a big shiny new one, and the NYSE/ICE has kept theirs open long past anyone’s expectations. It mostly comes down to handling big orders. While there are electronic mechanisms to facilitate these, and some sophisticated participants have even lobbied for everything to go electronic, the ease of transaction and price improvement on large orders still provides a lot of value.

The most active pits will regularly swallow orders of significant size. Sometimes these are market moving, but more often than not it’s simply the largest players using open outcry to get the best price for their regular business. They can have millions of deltas and seem big, but are just a piece of the puzzle in a large institutional portfolio.

If you tried to execute this electronically, there would be a lot of slippage because participants wouldn’t know how to react and instinctively raise their offers. When a buyer starts nibbling, providers pull back their price, the same way that AMM automatically charges more as size increases. If your broker has a chance to present the whole package on a platter for edge hungry locals, you will be able to negotiate a price on the trade that is either tighter or deeper than the screens (or both). You also don’t have to worry about partial fills if you do everything at once.

This balance changes over time as participants and regulators parry and riposte amongst themselves across the shifting sands of technology. Given enough risk tolerance, algorithms can consistently beat market averages over time. But sometimes there’s no substitute for speedy and simple.

Every market has its rules and practices that rewards a specific type of skill set. The big shouldered, loud, and confident traders won the most business in the pits, while the PhDs in fluid dynamics navigate the best amongst dark pools and lit screens. I’m still only halfway done, but it’s clear that J. Arnold Ross had exactly the right execution chops for the wild catting business.

_____________________

AMM Math on J. Arnold’s Land Buying:

Assume land is worth $5/acre, and there are 10,000 acres available.

The constant product says x * y = k. Value of Acres * Dollars will always be the same (k).

The pool should hold $50,000 and 10,000 Acres.

K = 500,000,000

If J. Arnold wants to buy 75% of the land, he needs to take out 7,500 acres, leaving 2,500 behind.

If there are 2,500 acres remaining, the dollar amount must obey the constant product formula

500,000,000 / 2,500 = $200,000

With $50,000 in the pool to start, J. Arnold needs to add $150,000 to be able to take out 7500 acres

J. Arnold’s Price / Acre = $150,000 / 7500 = $20.