Compound interest gets all the credit.

Earn 5% returns year after year and it really adds up. The Rule of 72 tells us that in less than 15 periods you’ll have doubled your principal. Rewards accrue to the patient.

While geometric growth looks great on a PowerPoint or retirement calculator, it’s the simpler maths that are the building blocks of an options strategy. The most important decisions come down to simple arithmetic.

A fancy volatility model with nodes and functions feels like an edge. Aggregating data in just the right way should be a lens into what the market will do. Maybe it’s just a gut qualitative hunch. No matter why you’re choosing to trade, everyone’s PnL is bound by the simple contracts and cents.

Price comes before size. Sum the long calls with your long puts, and be sure to double short strikes on your debit butterfly. Derive the market’s fair value for that spread with a few plusses and minuses. Assume the market is right. Now aggregate the markets’ width - every leg spreads the bid/ask further.

With an ephemeral fair value in hand, traders start negotiating on the price of liquidity. Three cents might be more than enough fat for deep delta options in SPY, but even tight near term call spreads will cost you fitty cents in MSTR.

Now that you’re ready to hit send, how many contracts are you buying?

Addition moves the prices to and fro, while contract count multiplies the exposure. If you can make a dime on a one lot, you can make a dollar on a ten lot. Risk of course, cuts both ways. Sizing itself isn’t an edge, but when mishandled even a crystal ball gets shattered.

Marker makers spend more time thinking about their size than their model. The fair value of the security is what the market says it is, stipulating pricing components like stock price, dividends, or interest rates. When your screens disagree, the first, second, and third inquiries should be that you’re doing something wrong.

Sizing is a direct function of the goodness of a trade. You do more of the good trades and less of the marginal ones. We all have our barometers calibrated slightly differently, but most of the time everyone agrees which are which. Competition has stamped out consensus.

To determine that juiciness, liquidity providers are informed and constrained by several variables. Price is an opportunity and a risk. If the market is indicating something is worth $1.00, with a tight confidence interval (bid/ask), then the opportunity to buy it for $0.50 seems like a home run.

If the offer was only $0.95, you might feel a lot better. Something priced so far away is a shrieking canary. Why me? What’s going to happen to this option that someone is so eager to sell at half its generally agreed upon value?

If you think the market is wrong, look in the mirror. Sure there are temporary dislocations, and undiscovered nuggets - the job of the market collectively is to find those. But if your base case deviates too much, the chances of being wrong increase. Size appropriately.

The number of contracts, or percentage of your position that you risk should increase alongside opportunity, but quickly plummet at “too good.”

Sizing needs to be flexible in the situation where too good gets even better. Whether you’re trading pairs that increasingly dislocate, or see an early trade start going against you, sizing is also about keeping dry powder. Sometimes the broker comes back with more. No matter what seat you are in, size must be nimble.

True edge is simple, repeatable, and most importantly small. Obvious is good for logic like “this ETF structurally pays contango every day”, but not great when applied to the idea that the delta of downside puts is off by 10 clicks.

Dealers must also look at the total size of the order to make their own appropriate sizing decisions. 10, 50, even 100 lots in liquid names go down easy. Digestible in their entirety, there’s no game theory about participation rights, and who’s taking this down. Or if there’s more to come.

When a significant counterparty needs the collective liquidity of an entity pit (or virtual IM network) of frenemies, elbow and keyboard jockeys start maneuvering. Sizing becomes a percentage of the order, with qualifications like “on a print” or “500 @ $1.00, 750 @ $1.05”

Market moving orderflow is a delicate balance of participation and risk management. Trading a piece of the orderflow is good for edge collection, and also diversifies the liquidity across multiple counterparties. Individual market makers aren’t bearing the entire risk of one trade, but also importantly brokers have more pricing power getting out of a trade if it’s spread around the community. That’s good for the customer and the dealer.

For traders the only certainties are death and risk limits. Taxes got solved by the Showdown at Gucci Gulch. Whether you’re at a hedge fund or flipping in your personal account, capital and the need to preserve it are the ultimate guardrails.

Defined by everything from greeks to gap risk, position limits exist to keep you in the game. They’re for when the home run position becomes a called third strike. Your broker or clearing company might have their own backstop, but that’s more about protecting their capital than yours. It’s up to each trader to calibrate their size and determine the PnL experience.

If the mandate is “don’t lose money” (looking at you Izzy), the edge must not only be rock solid, it can’t get blown out by a mis-sized trade. Edge is nothing if not probabilistic, and losses happen. Millenium’s returns are a tall order to match, but the strict focus on risk management and capital deployed are informative.

When you have other people’s money, risk takes on a different dimension. Your sizing has to account for the fact that someone trusted you, and isn’t going to care about the whopper justification you had. Management letters are fluff - everyone looks straight at the bottom line. Three percent doesn’t sound like a lot. But it compounds quickly, and makes an even bigger hole to dig out of.

Trading your own investment account should have that discipline. With any conviction other than “stocks for the long run”, sizing should be strict and limited. There are many opportunities in the market, and with some effort they can add sprinkles of alpha to your return. Too much enthusiasm and statements become cannon fodder.

The retail trader needs to size both their opportunity account and their trades within it appropriately. The opportunity account starts as a play account, and that’s a very small allocation. The sizing here can be a little bit looser. You’re here to play, and more importantly learn.

Feel free to trade contracts that can blow out several digits of your PA if you want to get spicy. Even 10% of a relatively large play account of 5% will be peanuts to what a diversified basket of stocks will earn over the long run. This is not a game though - any time you’re using real money you should have a trade plan. Certainly don’t keep topping a losing account off.

Different spreads deserve different sizing considerations. If you’re willing to lose 5% of your account on a trade, buying ten delta calls should be viewed differently than selling ten delta condors. The credit side has to consider margin as their risk limit, but the debit shouldn’t be purchasing calls with 5% of their cash. Consider discounting it by the delta - e.g. 10% of 5% of the portfolio. That lets you be wrong the 90% of the time the market says you will be.

It’s impossible to learn about trading, and new trading techniques, if you don’t get your hands dirty. That’s why a play account is necessary and important. It’s the tiny opposite end of the barbell from boring index funds.

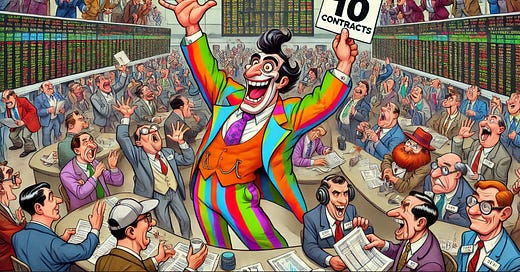

When Johnny Ten Lot raises his hand in the crowd, he is going to catch some heat. Capturing all $5 of edge there won’t buy lunch, let alone pay seat fees. Professional traders need to size their bets so they get a flywheel going where good risk management and opportunity capture balance to keep the whole enterprise afloat.

But no shame in throwing one lots around to test an idea. As the retail trader thinks about sizing, they need to ask themselves if the position is an investment or an opportunity. Am I allocating or am I speculating? The more actively you trade, the more gray that line becomes, so be careful. Early confidence and sizing up has destroyed many an equity curve.

Small and consistent is an exercise in patience. But successfully demonstrating that will allow you to increase the size of your opportunity/speculative/play account. A proven track record is very easy to scale up. Big and choppy doesn’t have to worry about that - the market will scale you down to zero pretty quickly.