(Update: Kelly Figures)

A wino is not the same as an amateur de vin. The further one finds oneself down the spectrum of vitis vinifera enthusiasm, the more important that distinction becomes.

There are beer snobs, peat heads, and zero interest rates even brought us water sommeliers. Outside an Evian vs Pellegrino vertical, for any enjoyer of alcoholic beverages, there must come a certain rationalization about quantity.

Fundamentally, alcohol is a poison. It may also be a tonic, but the key lies in the dosage. We’re all familiar with the idea that a glass of red wine has some positive effects on our heart and circulatory system. But we also know that binge drinking leads to more than a hangover, it has a nasty cousin in alcoholism and addiction.

For spirited lovers of the juice, it becomes a tricky balance. You can’t taste all the wines you want in one night, even if you’re spitting. Every individual has their own tolerances, thresholds, and risk factors. Two glasses for me, two bottles for Gerard Depardieu.

Over the last hundred years, alcohol intake has plummeted in Western societies. French soldiers in World War I would grumble about their 1L a day allocation, yet the average French adult drinks less than that per week as of 2020. Consumption is down 30% in the last 20 years.

The trends are mirrored in other countries, and the fundamental causes are similar. Only a minor part of the shift can be attributed to complementary goods like craft beer, whisky, or cannabis. Broadly there’s a push towards a more health conscious lifestyle, both from the top down and the bottom up.

Consumers are demanding healthier alternatives across the spectrum. Whether it’s organic and local food at the supermarket or more bike lanes in cities, it’s not just the fanatics spending $2M a year to live forever that want to improve their health and longevity.

Governments are also subtly and not so subtly nudging people towards more sober lifestyles. Duties levied, drunk driving enforcement, and stings against minors' purchases all have a chilling effect on consumption.

Whatever your opinions are about paternalistic policies, this is essentially a risk management question. By driving down the average level of alcohol consumption in a country, the curve is not just flattened, but the tails come in even more aggressively.

The tails has an interesting double entendre here. Options traders and statisticians talk about the tails of a distribution in order to define the shape of the outliers. Are they predictably fading into obscurity as a normal distribution like the height of a population, or are they wild and unbounded like a kurtotic price chart.

When you distill spirits, the condensed vapor coming out of the still must be separated and managed according to its makeup. The early whiffs (foreshots) are discarded like a warming griddle’s first waffle. The heads follow, which are particularly potent and used to blend and improve strength. The heart is when the best tasting spirits flow through. Finally are the tails, which tend to have off flavors and are best left excluded.

Whether you’re talking about trading or distilling, cutting off the tails is one of the most important decisions you can make on the production line.

When the CDC defines binge drinking as 4 drinks for a woman and 5 for a man, they are intentionally setting the bar low. Since these guidelines are taken about as seriously as speed limits, the policy is more about leveling the extremes than a specific recommendation.

Jancis Robinson is one of my favorite contemporary wine writers, and early in her career she penned a self reflective book discussing “The Demon Drink”. As a female, journalist, and wine trade employee, she had a triple threat of risk factors. During her objective review of the literature and science around alcohol, she highlights a study done in early 1950s France by a demographer named S. Ledermann.

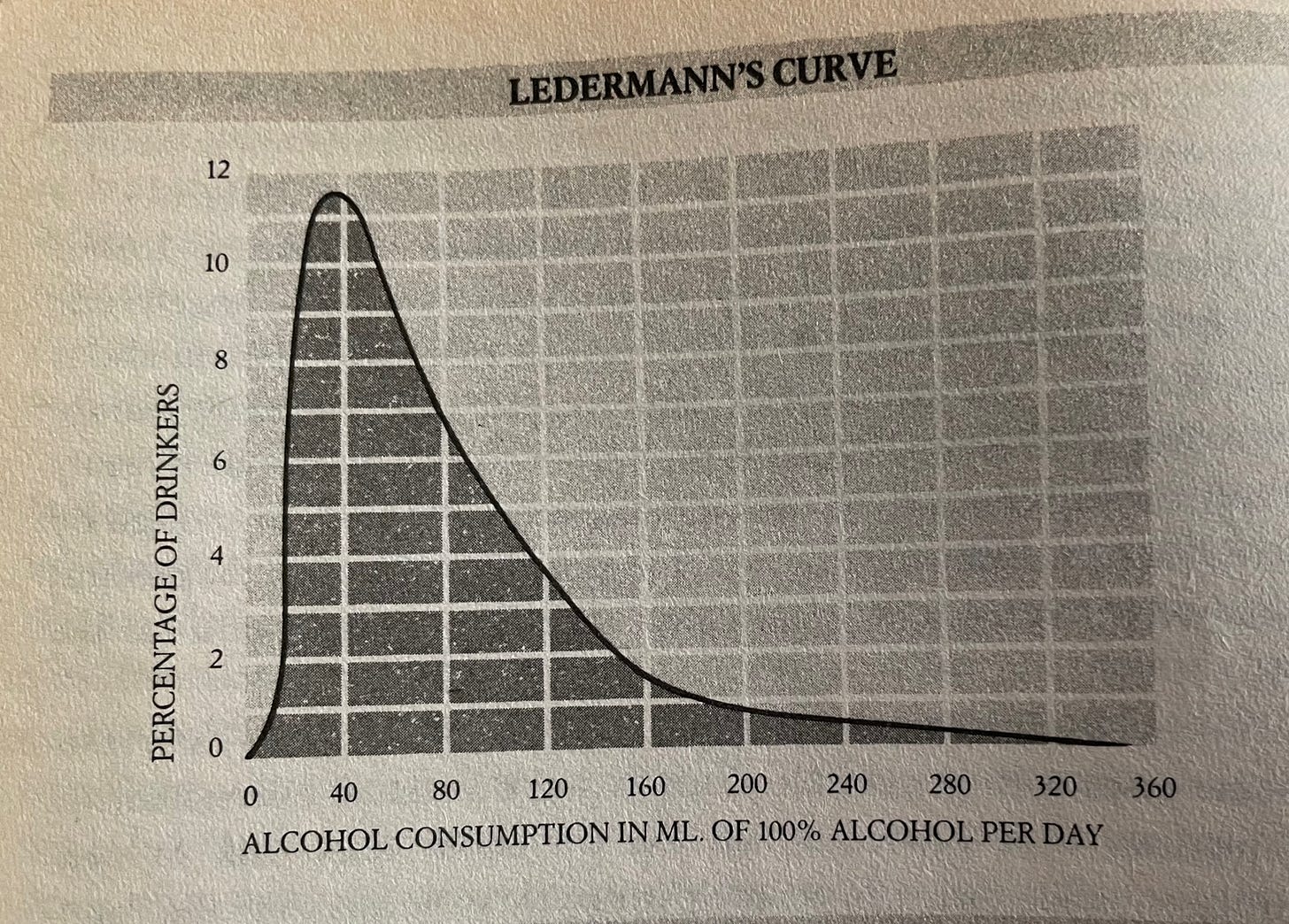

There are two major observations in Ledermann’s work. The first is somewhat intuitive, but a helpful framework. The distribution of consumption across a population will be lognormal, with a long right rail. Consumption is of course bounded at zero, and most of the population will cluster on the left side. The revelers extend far out to the right.

The second observation is the one with the greatest impact on public health and portfolio risk management. Any two populations with the same mean consumption will have the same prevalence of heavy drinkers - similar means have similar tails. But in populations of different average consumption levels, the tails are also proportionally different.

Further research in subsequent decades has not only validated Ledermann’s premise, but defined the magnitude of this relationship. It’s nearly quadratic. So a country with twice the mean consumption will have four times the prevalence of heavy drinking.

This sounds a lot like portfolio risk management to me. Absent discovering the El Dorado of Alpha, the main way to make more money is to take more risk. Ask for less edge or increase your size. With that you can expect to elevate the expected value but you will also raise the variance of PnL, and be more susceptible to large losses.

A very tight risk management policy isn’t going to have high PnL peaks. Countries where alcohol is tightly controlled aren’t usually known for their great parties. It’s also not going to have drunks asleep on the sidewalk every morning. Tightly buttoned up books don’t wake up to six figure gaps.

A looser risk management policy means cutting off fewer tails. Leaving more spice in your spirit. Most options risk policies have a gap or jump risk component. The OCC calculations for portfolio margin are based on theoretical shocks to price and vol. As market makers we’d run “gap risk” reports that showed your PnL at various shock levels.

Gap risk limits were dollar figures - you can’t lose more than X in a single stock up Y. As absurd as you thought that possibility was, traders would regularly buy nickel options or put on a spread to flatten this gap risk. It felt like throwing away a few hundred bucks, but that was the insurance policy you had to purchase to play another day.

Probabilistically I’d bet these were mostly “bad” trades. If you could simplify it, to cover $200k of gap risk, we probably paid $1,000 each of the 252 trading days each year. As a professional trader who has a business to run, these were simply an expense to reduce variance.

The reality of the world means rent is due monthly and the payroll has to be funded with cash and not edge. The pure arithmetic says you save the $1000 every day of the year, but if that once a year gap happens early on, you might not be around to save those other theoretical dollars.

Flattening those tails will come at the expense of foregone edge you could have collected and premiums paid by crossing the spread to close. But staying in business will allow you to compound your wealth and knowledge.

Because the world is wild and models can only approximate the infinite potential outcomes, we’re left doing a fair amount of subjective right sizing. The most famous framework for bet sizing is the Kelly Criterion, developed by John Kelly of Bell Labs - originally to deal with telephone signal issues. This relatively simple algebra relates the odds of the bet to your expected edge and bankroll.

The objective of this is maximal aggression - how can you increase your bankroll fastest. This is a double edged sword, as it can result in similar drawdown scenarios. For this reason most practitioners will only use a fractional Kelly system.

Partly this is because of the fuzzy nature of humans implementing strategies. Not only is it impossible to know what true odds or edge is, but having the stomach to ride the full Kelly rollercoaster is impossible.

The variance between various Kelly fractions is astounding. Ed Thorp has a great paper on his website with the full scenario details. Out of 2000 trials across 700 decision points, using a 1/8th Kelly resulted in returning at least the $1,000 bankroll 1978 times, with an average value of $2,000. Using 1/2 Kelly returned the bankroll 1930 times, but the average value was $19,000. Go full Kelly, and you only make money on 1752 of the occasions, but your mean is a whopping $524,195.

I’d sure take a cool half million bucks out of a $1,000 series of games, but do I want to lose $1,000 about 12% of the time? Raise the stakes and imagine you have $100,000 saved for a down payment on a house, would you take that same chance of losing that to buy the house(s) of your dreams with cold hard cash? (Unfortunately the real life odds are much thinner, and repeated less frequently.)

Where you cut the tails is going to depend on your overall risk appetite, capacity, and tolerance. Go full Kelly in the play account, and consider putting your down payment in T-bills these days. If you wait 6 months to find something, you’ll be able to buy a couple Moutons to celebrate with.

Even the CDC will admit that 5 drinks in a day isn’t going to send you to AA or possibly even have any long term effects. Your friendly risk manager hates bothering you about your gap risk. They’re both just watching their tails.

(Please speak to your doctor or financial advisor before taking anything I say too seriously.)