Depending on who you talk to, a wheel can mean a lot of different things. Practically, it’s the rubber treaded rim that moves you from point A to B. On TV it’s a game show gimmick. In crypto, it is the haloed flywheel that provides a self reinforcing propulsion for token ecosystems. Enough momentum to ex-machina sustainable value.

For options traders, the first wheel that comes to mind is the sell put, buy stock, sell call cycle that’s used to capture swings and options premiums. It’s a popular strategy because it fits well with the way we think about investment value - you go long the things you believe in, with a theta cherry on top.

Long comes with the sold put downside and lacks full deltas on the upside, but you get compensated with options premium. If you’re better than average at stock picking, misjudging options implied values can be compensated for with deltas and vice versa.

I carved out my own corner of infamy with a wheel for internal allocations on the broker dealer side. What trader doesn’t love a good dollop of randomness, and in bidding for the first shot at the next hot pharmaceutical stock, portfolio managers would get selected by a random weighted spin of their bids. Earning points with PnL for bigger bids helped, but stochasticity is a vicious mistress.

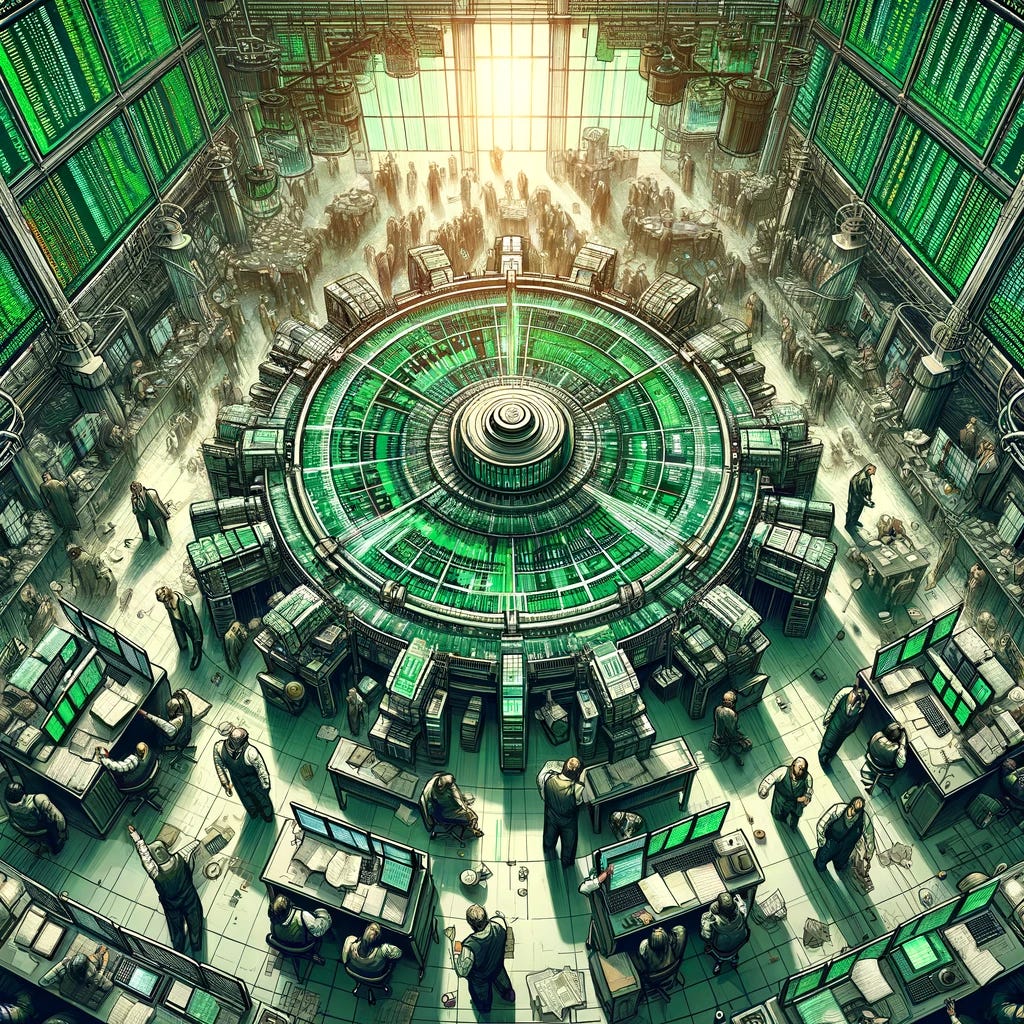

For all forty seven million contracts that tumble through the OCC universe every day, many of them of them are focused on an entirely different wheel. Roughly a third of volume is retail on any given day - more when there’s Gamestop glory to be had - and these get parsed out to liquidity suppliers via a random wheel.

Brokers make deals. They bring one side of a transaction to meet the other, and escape principal risk with a fixed transaction fee. On the institutional side they take high touch orders from large buy side desks like insurance companies, pension, or hedge funds and match them with liquidity providers, most of whom are registered market makers. People who want to do 5,000 contracts at a clip, meet the people who can.

Retail brokers can’t host a steak dinner for every client that wants to trade options. Robinhood couldn’t even afford to airdrop Ramen with an average account size of less than $4000. But what they can do at scale, and is very useful for the masses, is provide software and market access.

Everyone in the ecosystem wants more customers. Exchanges want the revenue per contract, dealers want the edge, and brokers want their PFOF. That third leg has been institutionalized via exchange marketing charges - pay the brokers a little bit on every customer execution so they bring in more customers - that funds customer facing tool development and client acquisition.

Good for the goose, gander, farmer, and fans of foie gras. But spending all this time supporting customers means brokers don’t have the expertise or infrastructure to optimize execution. They outsource this role to the market makers who kick them back the charges collected in their marketing pool.

Anyone suspicious of the underbelly of market structure will immediately see a conflict here. Dealers are boogie men who manipulate intraday prices, how much worse can it get if they’re also responsible for handling execution of an order they take the other side of? Is this how they’re front running me?

The details of how the orders get handled are very important. The wheel liberated the Sumerians, and showers the rewards of competition on retail options traders. Sold orderflow is what brings retail traders to the table, without it they would be trading a vastly different market. No pretty charts in your mobile trading app, dollar wide markets, and strikes that are only listed at 1% and 100% out of the money.

Brokers are retail's best advocate, pitting the various market makers against each other. By randomly allocating orders according to fixed overall percentages for each participant, they control the choke point and make their suppliers dance for their supper. This is what summons the liquidity party, and supports a vibrant market structure ecosystem.

A broker starts by negotiating payment terms and execution quality (EQ) targets from the different dealers. More payment in cash means EQ will slip; liquidity providers need to collect more edge to afford higher payments. If a broker demands too much price improvement, the market maker may balk as that drops below a sustainable expected value. You don’t pay $0.49999 cents for a $1 coin flip, no matter what SBF says.

As each 1, 5 and 10 lot comes in from the terminals, it goes to the next firm who’s due contracts. Which order a market maker gets is completely random with respect to the timing of a particular broker’s customers but also who amongst their peers is up next.

Putting all of the market makers on a wheel lets brokers squeeze and compare them. Interested in upping your slice on the wheel from 20% to 25%? Last month the dealer around the corner delivered an average EQ that was 2 points better on the same payment, can you match that?

There are even wheels within wheels. Have you noticed your broker is particularly good at execution of single legs but you never get price improvements on a spread? It’s likely due to how their downstream orderflow deals work. There is even separation between certain tiers of issues, or exclusive carve outs for SPY. It’s hard to price improve a penny wide market, so there are different expectations. 0DTE dynamics are being actively negotiated as this unique slice of flow evolves.

This wheel, and the competitive analysis it allows for is a boon to all involved. While market makers might gripe about the unforgiving compression of edge, it also provides a level playing field to demonstrate their prowess.

Skeptics may continue to point out that an oligopoly of wholesalers is hardly any better, and wouldn’t the collusive dynamics that friendly pits allowed for just make its way to the screens? Besides all this EQ analysis is ex-post and requires a large enough sample that the abuses may persist for material amounts of time.

The longer term game of working to provide better execution and gain retail market share is checked by the competitive dynamics at every single trade. Wholesalers who get an order dropped at their doorstep from the wheel, can’t simply take the other side, they need to expose it to a price improvement auction where anyone with a feed has 100 milliseconds to produce a response.

Very little slips through the cracks when a dozen or more participants are also looking to collect edge. Even after a hard day scalping ticks to stay afloat, if there is any padding left after meeting your EQ targets, someone else will box you out if the order is priced too favorably.

The wheel methodology can also be used by individual firms to manage their vendors. Stock execution for market makers, buy side desks, or anyone else that deals in millions of shares a day becomes a game of fractions of basis points. With everyone’s algorithms competing with each other to get a hair better than VWAP, the bag of tricks must constantly be refreshed.

The easiest way to see who’s best is to have a bake-off organized by the wheel. As with any study it’s important to make sure your samples are independent and not biased with one type of flow or another, but after only a few weeks the results can be illuminating. Of course this transactional analysis will also be demonstrated by brokers themselves, each in a slightly unique method that has you comparing Red Delicious to McIntosh, so locally grown is always better.

Designing an orderflow wheel takes more than a few spokes and rubber. Systems nerds will appreciate the nuances of allocating a random process against fixed targets. At any given point in time, there will be a sum total of orders, each participant will have received a certain number of contracts, and those ratios will be either under or over their target.

If a ten lot comes down the pike, should it go to the next participant that has a deficit to optimal, or should it go to a person that has the deficit closest to ten? Send it to who’s due, or who gets closer to true? In a world with only two participants, do you adjust for the fact that one fifty lot is less desirable than getting the next fifty one lots? Bin packing problems are funny.

The wheel spins customer orderflow into execution quality. It keeps liquidity providers constantly on their toes to defend their share of the pie. It does also have some unique quirks. Any set of rules will be managed by the participants, and on individual orders there can be weird comparisons, e.g. price improvements with one broker but not another.

One issue might get price improved aggressively because it has extra fat that can be stacked against tighter margins in other issues. It accrues to the market maker in the same bucket, but those individual orders are getting a different experience. This corner case is a more than acceptable outcome given the overall dynamic, as ultimately even a customer strategy shouldn’t be life or death based on a specific fill.

Turning in the background, the wheel in the sky not only delivers price improvements that customers can see in their statements, but the structure and rules of it give confidence in ongoing executions in a fast moving market.