The simplest of algorithms is called the identity algorithm.

A function that only returns the value it was given. identity(x) = x. No if/then or conditionals, just pass along what you’re given. A one line code game of telephone.

That’s a market order. Take the price I’m given, and pay that. No decision making or routing, just trade where I can. If necessary take multiple levels, because the buy price just keeps refreshing to the new offer.

Add in a condition and you have a limit order. If price < X, buy. It doesn’t take long before you start thinking of other behaviors or logic you could program in here.

Now we have the makings of a real equity trading algorithm. While algorithmic trading does involve a lot of work from quants doing granular research and building complex decision trees, it doesn’t always have to be so fancy.

If you’re trading small quantities of shares, there isn’t much need for an algorithm. The decision is more about whether to buy or sell at all. But once you’ve made a decision to trade a certain amount of shares, if that’s of any sizable quantity you want to do more than lifting bids or slamming offers.

Equity execution used to be done by hand, there were talented traders who could feel the market. As much as it bothers my efficient market sense, there are absolutely tape watchers that can manually execute an order better than others, Jesse Livermore style.

But passing this off to little bots makes a lot of sense. They can automatically feed in dozens of signals and quickly cancel/replace orders across a multitude of venues.

The main reason to execute using an algorithm is to get a better than average price. Better is obvious, but what arithmetic do you use to come up with average? Benchmarking against either the order start time or the close make sense as absolute marks. But that can be rather arbitrary.

What you want for a better than average price is something that reduces the arbitraryness of execution. Sure we all wish we were Marco, the kind of guy that could call every top and bottom tick, but lower variance in average pricing is more desirable than the risks of perfect.

Today in the Backtest Notebooks we’ll dig into the almost simplest of algorithms - the Time Weighted Average Price (TWAP). If you TWAP options positions over the course of a day, how does that change outcomes, and why do we care?

If you want to be semantical, even a market order or a limit order could be considered an algorithm. As short as it may be, there is a decision tree. You can add certain qualifiers like “Post Only” but that also still falls on the order type side of the line.

I’ll call an execution algorithm something that has “child” orders. If you’re chopping up a bigger “parent” order into smaller slices, and then executing them independently, that is true algorithmic execution. The resulting logic chain can be very complicated, tracking percentages of volume, adjusting each order’s venue; but we’ll start with something simple.

WAP stands for weighted average price. There are several flavors of this, but the two predominant versions are volume and time weighted. The idea behind this is simple - use it when the goal of execution is to get a price that is as close to the benchmark average as possible.

It’s important to note the uncertainty principle here. Execution necessarily impacts the benchmark you’re measuring against. Market interactions will increase the volume, and move prices. Even just posting an order creates an imbalance that many high freak tape readers will pick up on.

With a TWAP (time weighted) you don’t have to worry about reacting to that. A TWAP order will typically take the order size, time remaining in the day, and slice up the execution equally across intervals. Time ticks in a very predictable way, and the goal is to buy a little bit at each point in the day.

There are many reasons why you’d want to do this.

#1 : You have a size problem. If the trade is relatively large compared to the liquidity, you’ll want to split it up. Market makers in equities or options are skittish - if they see order size greater than the display, they’re going to fade quickly.

Liquidity providers are of course keen to these order types in the market, and if they see a large order that seems to be TWAPing, they will absolutely adapt. But because it’s tranched out over time, they have many opportunities to hedge the risk and digest the order. Maybe even lean into it.

#2: Better to be wrong with the crowd than right on your own. One cynical view of this in asset management says managers herd with the benchmark and just want to keep their jobs. Why buy the open and risk a big down day (close and miss the up day) when you could just buy a little bit each step along the way.

There’s some truth to that. But I think there’s also a self contained justification where as an individual you don’t want to put too much pressure on any single decision. Whether your strategy is a hard earned nugget of edge or a simple rebalancing, there might be a big dollar amount behind that final button. Why not break that up into a lot of little marginal slices.

#3: Compliance rules everything. It’s not just the justification to your revenue focused boss, there is a third party who needs to consent that this market coupling follows the rules. While CCO sign off is only a concern if someone is paid to read your instant messages, TWAP usage is valuable to understand as a regulatory structural force in the marketplace.

If the order gets too big, you go beyond nudging kinks in price discovery, massive size becomes market manipulation. Any savvy practitioner knows how their traded market will behave with a given size and order entry behavior. Even if you’re a genuine buyer of something, acting conveniently sloppy and pushing the market around will raise red flags.

#4: It improves the return profile of your strategy. Here’s something everyone can get behind. Note how I carefully added profile - a TWAP does nothing in the absolute return sense. What it does is reduce the variance of your returns.

This isn’t going to double your sharpe overnight, but anywhere you can reduce arbitrary volatility is a win. Price discovery is a process, and giving too much credence to any one point in time might work itself out in the long run, but adds a little extra chop.

For the altruistic, a TWAP order is a gentle interaction with the market. Recognizant of its size, it lets the liquidity pace itself. Even if you win the battle by rocking the boat, intentionally punishing dealers will raise the price of spreads for everyone.

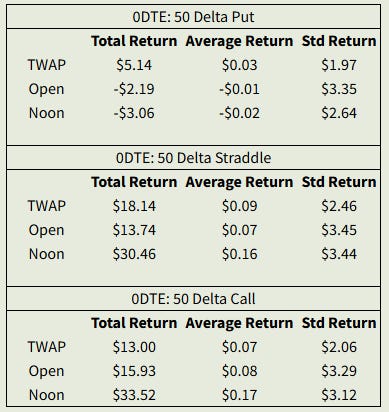

To prove this point, I ran a couple of simulations on a 15 Min TWAP for SPY options over the past year. These strategies are very naive but it’s more about pointing out the variance component. Buying calls over the course of the day wins because for the last 10 months the market has generally closed higher end of day. This compares the average TWAP, an open buy, a noon buy all to the closing mark. If your books settle on that close how much does each strategy differ from that?

These are obviously not good strategies, because the standard deviation of returns is wild. But it’s always less with a TWAP. The math behind way is fairly intuitive, but a little bit of reduction in variance can go a long way.

Note that these are per share dollars earned over the entire time. So an average return of $0.09 cents says buying the straddle all day and selling at close would net $9 per contract to your account.

Beyond the variance reduction, it’s a fun lens to look at the market path. If you see these strategy returns, what does that say about when and where the market moved year to date? (For more on this kind of thing, I’d highly recommend the Options Structure Dashboards at VolVibes.)

You don’t need to have a 100 lot to buy to consider the impact and uses of a TWAP. Even if you have a two lot - trade in the morning and afternoon. Maybe you even want to rebalance over the course of a few days. I’ve referenced the lump sum argument many times, but psychologically it’s a nice relief to spread the weight of the decision across a few clicks.