The Black Album was Jay-Z’s mid-career crisis.

Claiming that the game wasn’t hot any more, he dropped these farewell tracks and planned to walk away - there was no more competition to fuel his creative drive. (Nas disagreed.) In between bars about his 99 problems and Shawn brushing the dirt off his shoulder, curiously placed right in the middle of the LP is a song called “Encore”.

Kayne opens the song up, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney even get songwriting credits because the Beatles song “I Will” is sampled. Rapping about his all time highs and triple deck yacht lifestyle, he frames his discography as a “grand opening, grand closing”. Reasonable Doubt and The Black Album bookend a decade of bangers.

Grand openings are everywhere. The debut of a store, park, or stadium is a well feted trope. New beginnings are something to celebrate with banners and fireworks. Closing time is when prices are chopped and you don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.

Along with HOV, options market makers also celebrate a grand closing. It’s the completion of a round turn, to borrow the futures lingo. Some brokers will even give you free commission when closing your positions. The books are clean and margin is reset - hopefully at a profit.

For dealers there’s a bit more pricing power against a customer who is looking to close out their contracts. A constrained counterparty is someone that is more likely to pay up. These handcuffs come in various different shapes and sizes, but they all ultimately mean there’s a bit more edge that a dealer can squeeze out.

When I was a trainee coming up on the AMEX, there were still a handful of cash indices that traded on the floor. These precursors to ETFs were clunky to trade, as rather than having one underlying to hedge, there was a basket of stocks with their various component weights that had to be traded.

Clerks raced to buy a dozen different stocks after their market makers sold calls. Slippage was brutal. There was always at least one component that missed, and we spent frantic minutes in the booth refreshing the “Basket Offness” report to see which laggards had whiffed. You dreaded having to report to a trader in fast market mode that he missed 5000 deltas and stock is up a few bucks - perhaps worse than the $10,000 burrito.

All of these hedging costs were thus baked into the pricing. The options had wide bid ask spreads to accommodate all the pennies and nickels you gave away in transaction costs and delta management. Making pricing even more opaque, the official values were only published every quarter hour. Everyone had #REF littered spreadsheets wired to Bloomberg to price these real time.

CYC was the Morgan Stanley Cyclical and XAL was the AMEX Airline Index, but the real high flier was the “Mush”. The MSH - Morgan Stanley High Technology Index - was legendary for its volume and profitability.

I’m too young to have been trading in the dot-com boom, but the stories still echoed across the floor. Wild price swings on ever increasing stock handles were catnip for the hungry and fearless. It took nerves of steel to trade names like these, but the rewards were epic. It took more than a decade before another trader eclipsed our MSH Master in gross PnL.

Twenty plus years ago there were fewer counterparties and less strikes. This made sleuthing out an order's intent a lot easier. Big open interest on a line would inevitably get rolled, and oftentimes you even knew which broker was going to come in with the order.

When the big customers came in to roll, the pit didn’t even need to give a sideways glance, you knew which way this market was going to skew. If the screen market on the old month was $45.00-$55.00 (yes, seriously, they were this wide), and the new month was $75.00-$85.00, fair value is right around $30.00. The screen quote would be $20.00 - $40.00.

A broker’s job is to do better than the screens, and market makers are happy to oblige and compete for the biggest slice of the best flow. Price improvement is subjective. If the customer was long the old month, they’d be selling that, to buy the new month. Knowing this, rather than evenly price improving a quote to $25.00-$35.00, a savvy pit would price it $30.00 - $40.00. PMOB - Pay My Offer, Broker1.

The customer needs to roll this trade either for reasons of mandate or margin, and has to give up that extra edge to do so. Rather than selling at $35.00 for $5.00 of edge, reading the customer correctly doubles your collection.

Electronification of markets, multiple listings, and better underlying products crushed these obscure indices. The last print on the MSH was September 8, 2017. But customers with a formulaic trading pattern have not gone away.

A customer isn’t always a person sitting behind a keyboard making discretionary decisions. Popular products like VXX are ultimately customers in the derivative markets too. In order to provide their advertised exposure, Barclays (issuer of VXX) needs to make the same trade every single day. It’s as predictable as the closing bell.

VXX is designed to be a tradeable VIX proxy. You can’t buy the VIX, but you can hold VXX - definitely not investment advice, look at the long term chart.

The reason this parabola tails into an asymptote is because of the ongoing trading costs of the ETN. In order to mimic the daily movements of the VIX, every single trading day the fund must rebalance, buying and selling different futures months to keep a steady weighting of thirty calendar days.

Guess which way those markets skewed when the same broker came in just before closing time?

While a capacity constrained closer might be fleeced for a few extra shekels, ultimately both sides are happy to shut down that risk. Profit or loss, the position is no more. Greeks are flattened and margin capital liberated. An opening trade - particularly in a product with few other positions - is a new reason to keep you up at night.

Pattern traders get skewed markets, openers get wide markets. In a product with little open interest, a dealer can’t predict which way a customer is going or what they know that he doesn’t. An opening trade is a bet on some future activity. Even if it’s just a hedge, the orderflow is marginal demand that increases the price of variance.

With 40 million contracts trading hands on any given day, this quickly becomes an OPRA soup. No single market participant has perfect insight into what any given piece of orderflow might be doing or how that fits into another’s overall book.

Opening and closing don’t have to be explicitly literal. Seeing large open interest on a line means a dealer can be confident of the future liquidity. More open contracts means more eyes, better pricing, and easier outs.

When open interest is declining, it means liquidity is leaking out of the product. This happens when old contracts fall off at expiration, or customers close out positions without opening new ones. Activity equals better pricing, which helps customers and dealers alike.

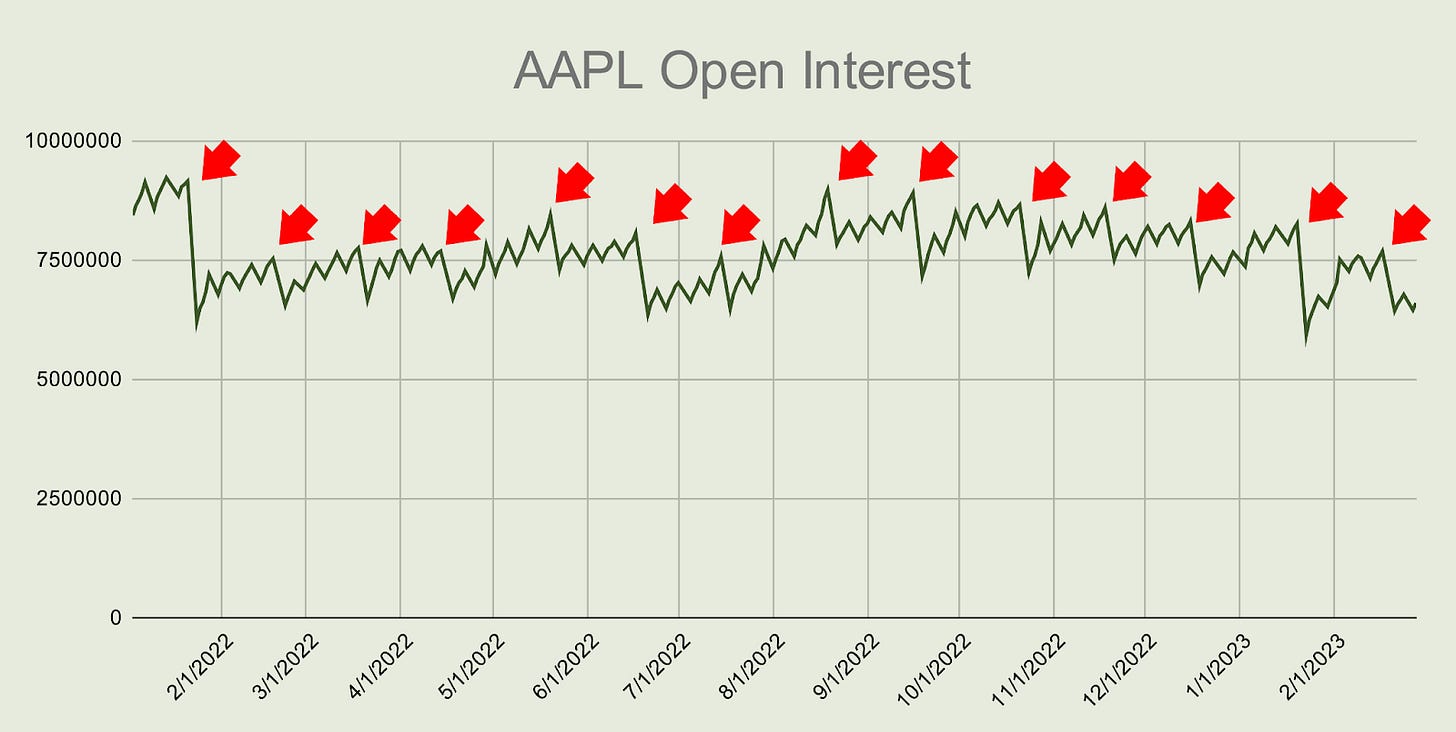

Tracking open interest changes is an important tool in the kit of anyone trading options. While there’s not much to worry about in SPX or NDX, liquidity ebbs and flows in even the most active products.

AAPL consistently ranks as the highest single name in my LIQ Index, and on any given expiration approximately 15% of the OI falls off. For a big expiration like January (LEAPS that have been listed the longest), that number hits 30%. If that’s not constantly refreshed with new volume, the Cupertino kid will go the way of the Mush. Fireworks not included.

Broker can be replaced by other words, also beginning with a B, depending on one’s temperament.